Previously I outlined why the ‘PTL’ approach to waiting times management is a labour-intensive way of achieving sub-optimal performance, and why it should be replaced with a rules-based approach to patient scheduling that optimises waiting times continuously without needing regular intervention from senior managers.

Here we will illustrate the point, taking a real NHS waiting list and (in a simulator) converting its management to the rules-based approach. We will see the 92nd centile waiting time fall from 14 weeks to 6 weeks, even though the size of the waiting list has not reduced. We will see how the biggest improvements are seen in the first month and how gains are sustained indefinitely (so long as the waiting is not allowed to grow).

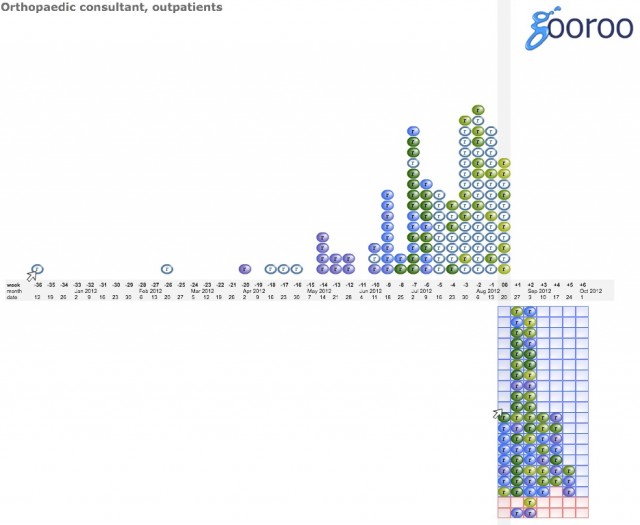

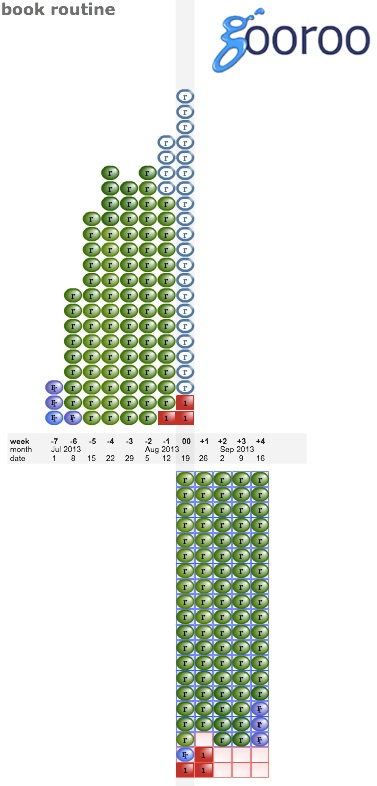

So let us start by introducing our real waiting list. Here it is, and it’s the new outpatient list for one consultant orthopaedic surgeon.

Let’s take a quick tour of this image. The vertical grey stripe shows the date of this analysis, which in this example is the week beginning Monday 20th August 2012. To the left we have the waiting list; each blob is one patient, and they are sorted according to their referral date (so the longest-waiting patient at the far left has been waiting 36 weeks). If a patient does not have an appointment date (like the longest-waiting patient) then they appear hollow. When they are given an appointment they turn solid, and a copy of the patient is placed on the appointments diary; the appointments diary goes off to the right and into the future.

There are 121 patients on this waiting list, and the 92nd centile waiting time (i.e. how long the 112th patient has waited) is 14 weeks. So that is our starting point.

How are this consultant’s outpatients being scheduled?

Looking at the appointments diary (the grid to the lower right), there are plenty of empty clinic slots in the current week. Then for the next two weeks all slots are fully-booked, and after that there are plenty of empty slots again. So it is not clear, looking at the appointments diary, what the rules are for offering slots to patients.

Looking at the waiting list (to the top left), we can see that a majority of short-waiting patients are unbooked, then nearly all the longer-waiting patients are booked, and the few very-long-waiters are mostly unbooked.

So it looks on the face of it as if this is loosely a partially-booked system, booked about 3-4 weeks in advance, with efforts being made to book patients in date order. However slots are not being fully utilised, many short-waiting patients are being booked ahead of longer-waiters, and the very longest-waiting patients are not booked. So there should be scope for improving the management of this consultant’s list if we used all the available clinic slots and booked strictly in date order.

To mimic the possibility that patients are genuinely choosing not to take up offers of early appointments, we will assume that some 10 per cent of patients rearrange their appointments at short notice and put themselves back in the queue. (It is of course possible that the very-longest patients, who are unbooked, are choosing to delay their appointments by several months, but the delays are so long that it is surely legitimate to ask whether they should have been referred in the first place.)

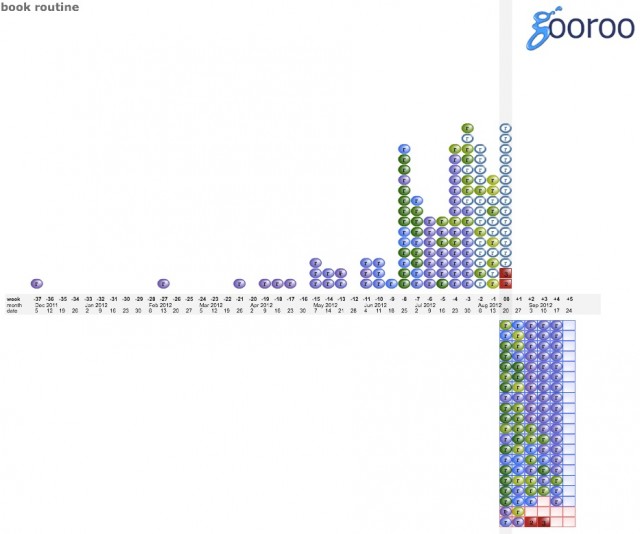

So let’s hand this waiting list over to the computer and let it do the booking. (If you want to do this kind of analysis on your own waiting lists, the actual waiting list was loaded up into Gooroo and run using our rules-based booking simulator.)

What’s changed in this picture? We’ve filled all available routine appointment slots (the blue ones) up to 4 weeks ahead, by booking patients in strict date order. Also, more patients have been referred, including a couple of urgent patients (shown in red); those urgent patients have been booked into urgent slots (the red ones). So we can already see how things are going to get better: over the next few weeks all our longest-waiting patients are going to be seen (unless they cancel).

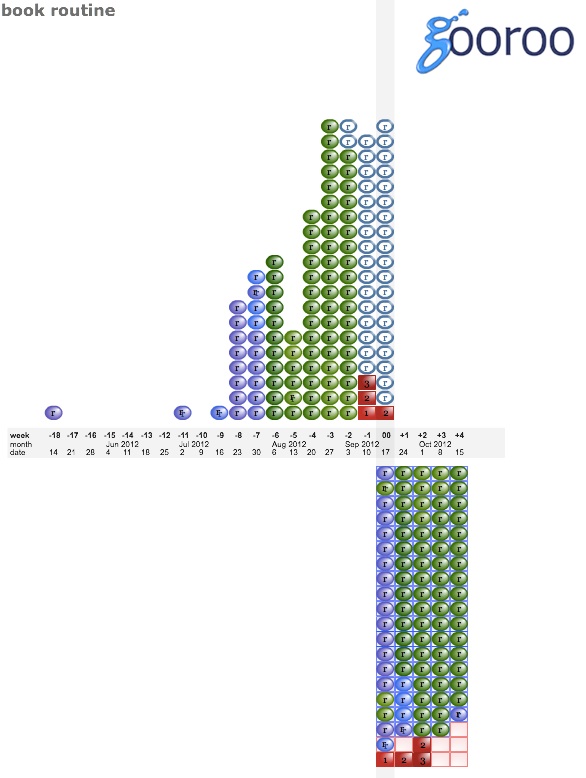

Fast-forward a few weeks, and things are looking very different:

Most of the long-waiters have been seen already, and there’s just one patient from May still waiting. We did have a couple of cancellations who were put back on the list (they are shown with a double letter, to show that they’ve been cancelled). When we hold this week’s clinic, we’ll clear most of the remaining long-waiters and things should look a lot better.

One week later:

This is the new normal shape for our waiting list, under rules-based partial booking up to 4 weeks in advance. If we chose to run a fully-booked service instead, offering patients a choice of slots in up to 3 different weeks (which is compatible with Choose and Book rules), waits would be a week or two longer but otherwise in a similar position.

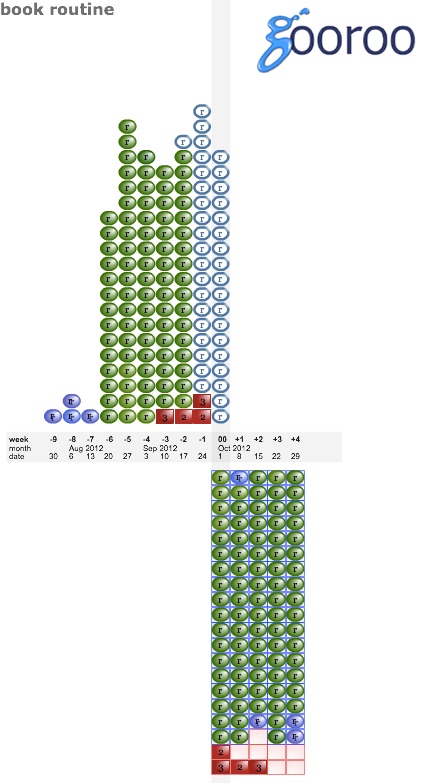

This is sustainable, so long as the size of the waiting list does not grow. Here is the same list a year later:

We’ve achieved a dramatic reduction in waiting times by implementing some relatively simple rules for booking patients, continuously as they come in. No weekly PTL meeting, no senior managers fire-fighting, just good clerk-level administration.