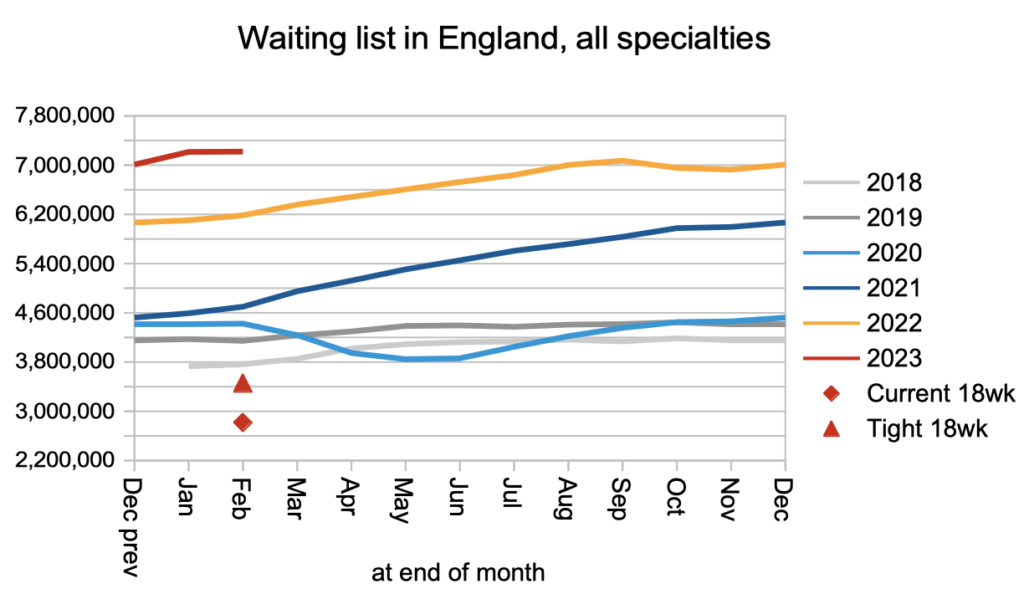

The English elective waiting list grew very slightly again in February, to a new record size of 7,218,001 patient pathways. Waiting times eased a little from 46.6 to 46.2 weeks, based on how long the first 92 per cent of the waiting list was waiting at month end.

Analysis produced for Health Service Journal by Dr Rob Findlay, Director of Strategic Solutions at Insource Ltd and founder of Gooroo Ltd

The next national target is to eliminate waits longer than 78 weeks by April, and on the face of it there is progress being made, with over-78-week waiters falling from 45,631 to 29,778 patient pathways during February, with the provisional statistics for 19th March showing a further fall to 20,101 pathways. However there is some doubt whether these numbers fully reflect the patient experience, following contentious new guidance issued last autumn which made it easier to omit some patients from the reported figures.

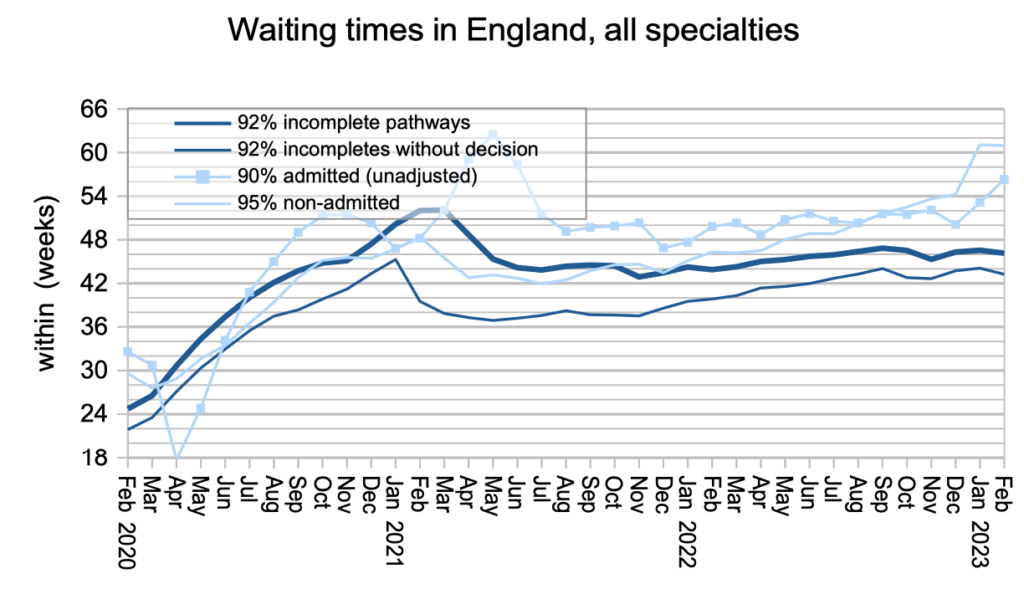

Long waits cause clinical risks for patients, which is why reducing the very longest waiting times for treatment is so important. However it is also important to reduce waiting times for diagnosis, because an ordinary (non-cancer) referral is the second most frequent route to a cancer diagnosis, and the disease is likely to progress during the wait. So it is good news that the national waiting time to diagnosis and decision has stopped rising, although it remains far too long and reducing it should be a higher priority than it is.

In the following discussion, all figures come from NHS England. They do not yet reflect revisions to the data for the year prior to September 2022. For analysis of waiting times performance at a particular organisation, visit our reports page, or our map of the latest elective waiting times across England.

The numbers

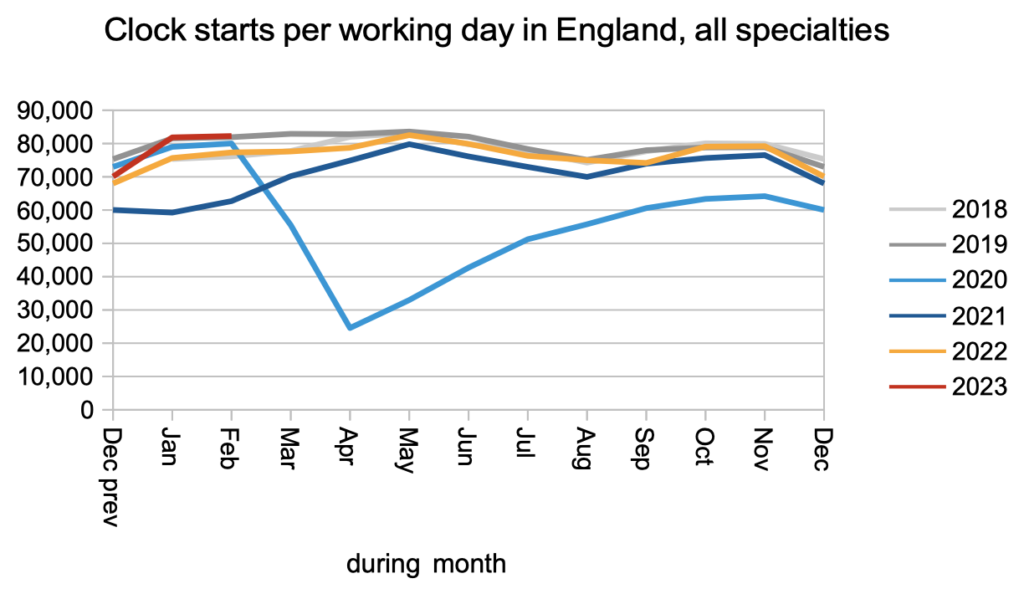

Elective demand has returned to pre-pandemic levels, as shown by the number of patients starting new waiting time ‘clocks’. There is still no sign of pent-up demand from the pandemic surging back.

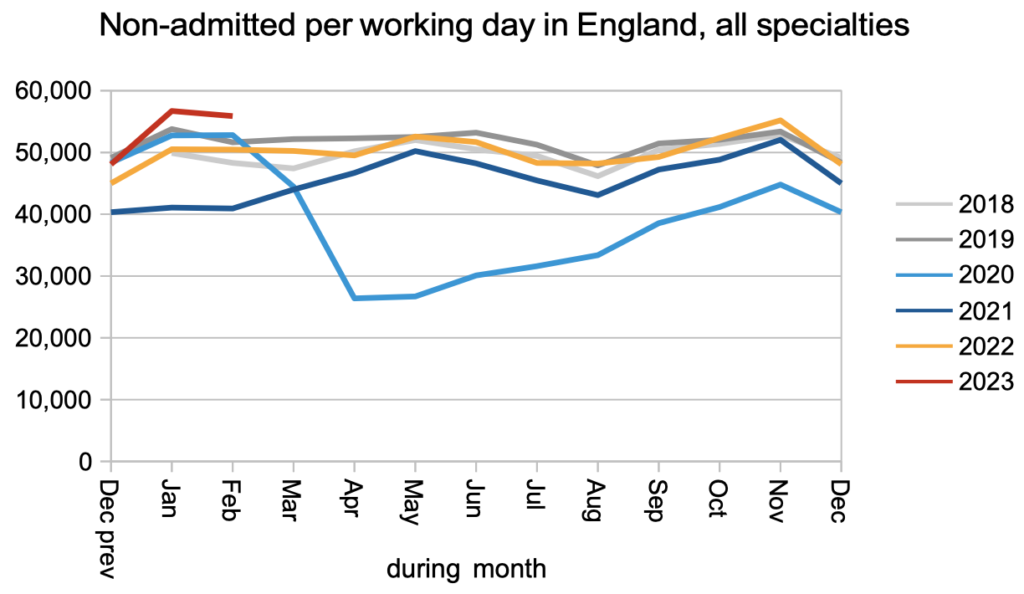

The rate that patients are discharged from outpatient clinics (or otherwise leave the waiting list without being admitted for treatment) is higher than pre-pandemic, which is a good thing. As we will see in the waiting times chart below, this is benefiting those patients who are waiting the longest for a diagnosis.

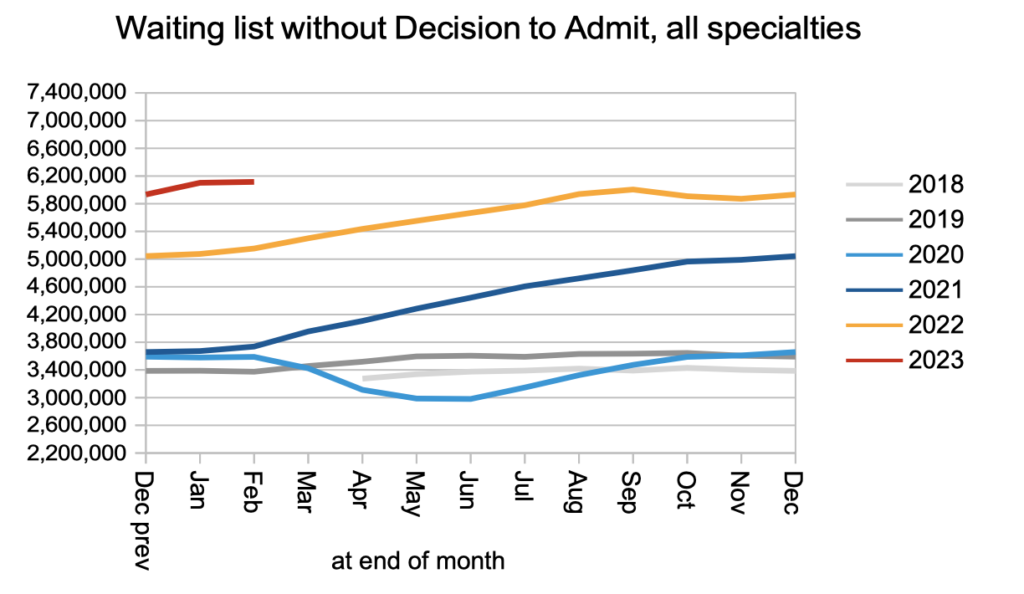

The number of patients waiting for a diagnosis and decision has stopped rising, but it isn’t yet falling. Clearly an even bigger effort on non-admitted activity will be needed before today’s excessive waits for diagnosis can be reduced to reasonable levels.

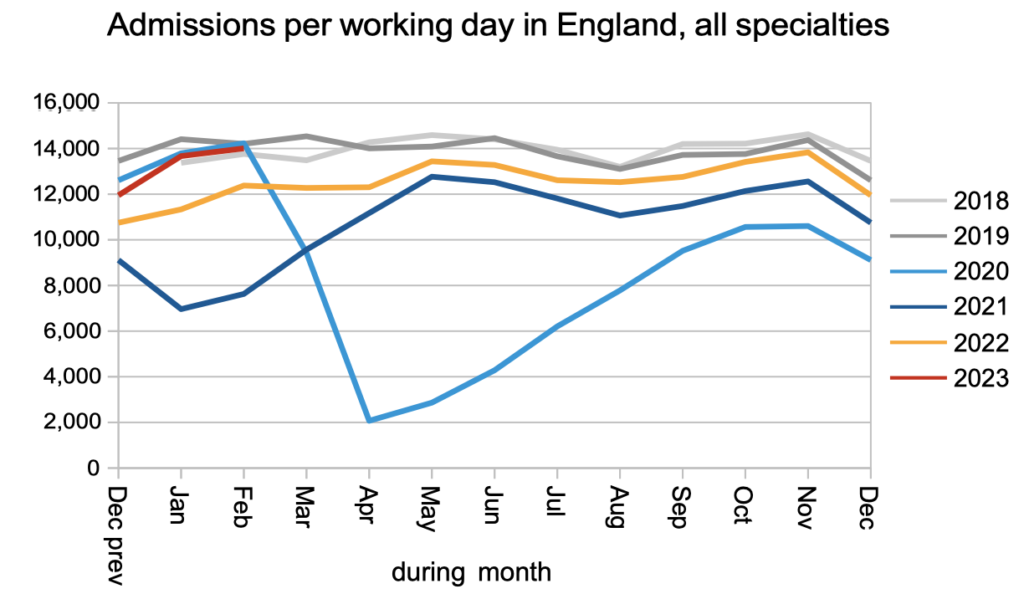

Elective inpatient and daycase admissions have just about returned to pre-pandemic levels.

The net result of pre-pandemic demand, and slightly higher than pre-pandemic activity, was a waiting list that grew only slightly in February. Or to put it another way, we are still waiting for a proper elective recovery to begin. The red triangle in the chart below shows that the waiting list needs to roughly halve before the 18 week target would be achievable once more. (Yes, 18 weeks is still the statutory target.)

In the next chart, the thin pale blue line shows that very long waiting patients are finally reaching diagnosis as a result of the higher non-admitted activity noted above. Waiting times to diagnosis and decision fell slightly as a result. This is good, but there is much further to go before a safe waiting time to diagnosis can be reached.

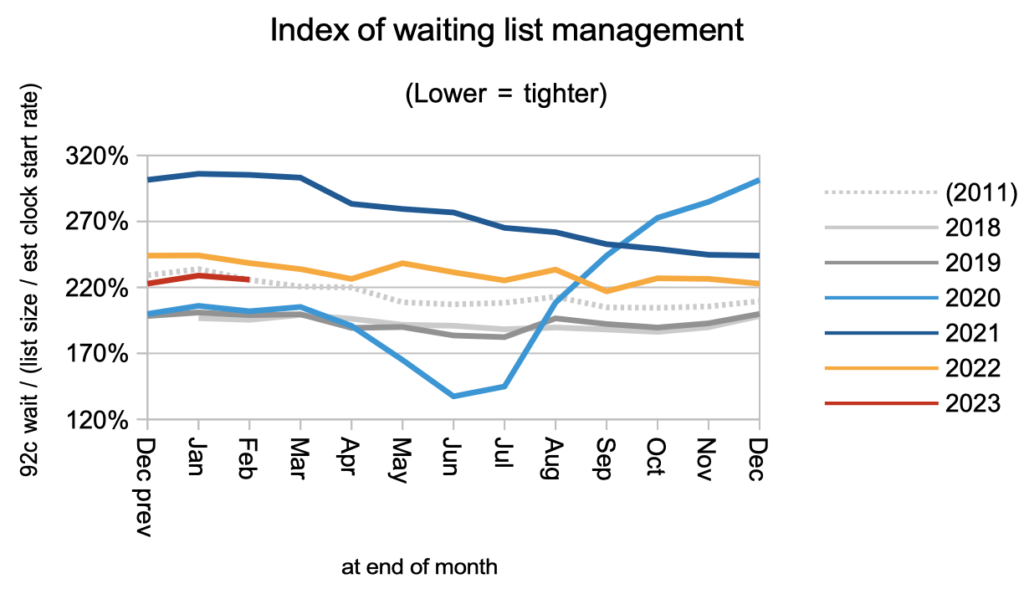

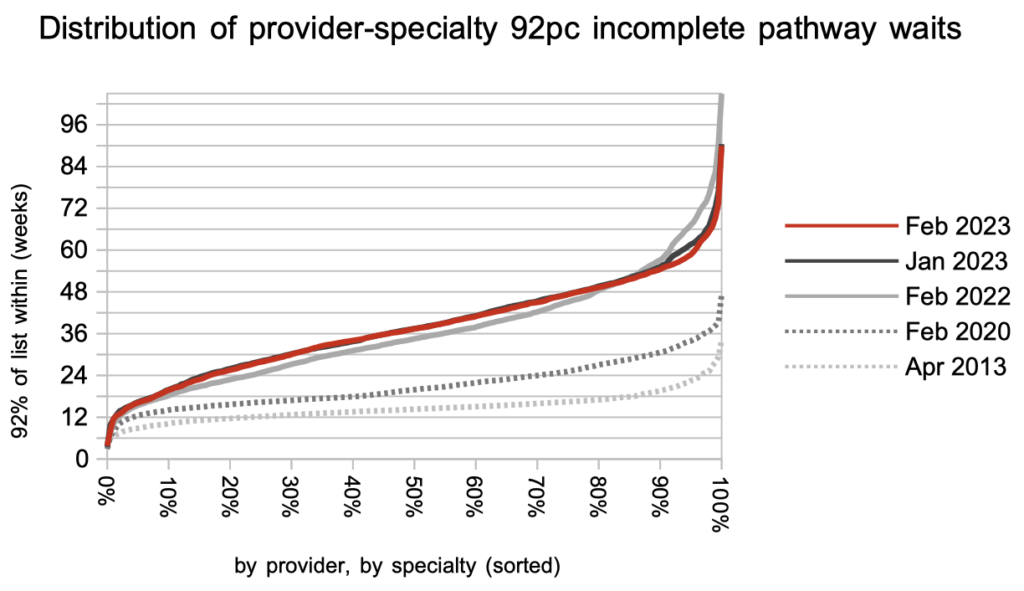

Waiting times are a function of both the size of the waiting list, and the shape which is reflected in the next chart. The shape remains poor compared with pre-pandemic, mostly as a result of the highly variable waiting times seen around England.

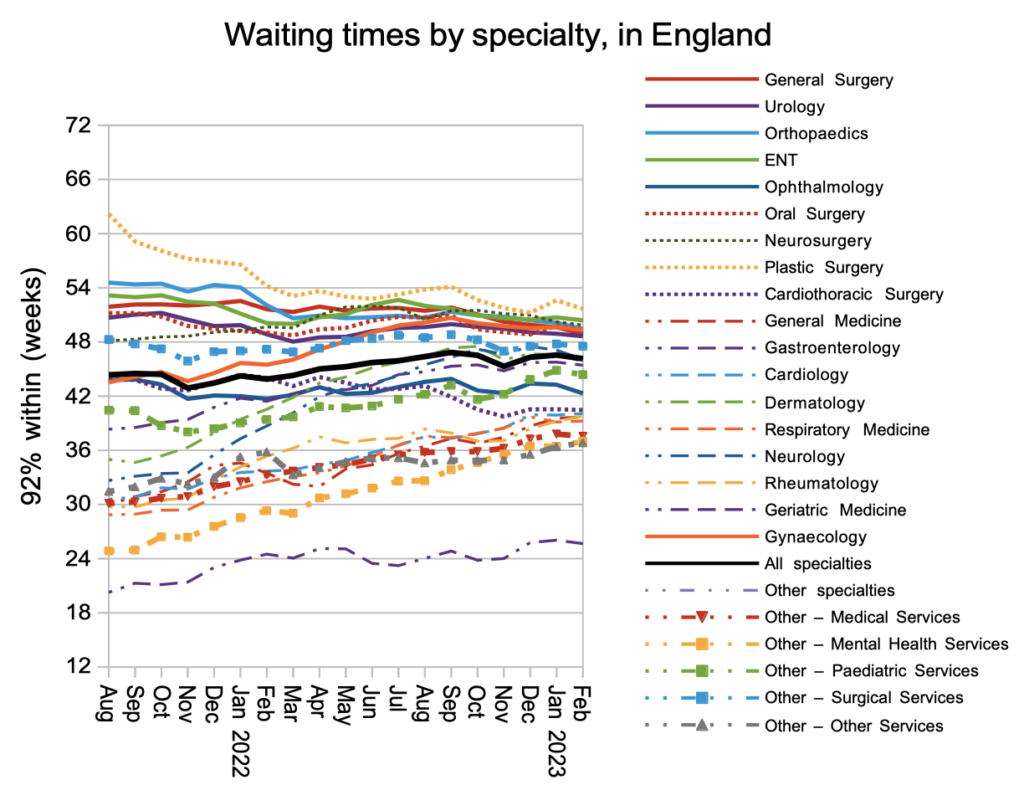

The longest waiting specialties have been improving at national level, in line with the targets to reduce excessive referral-to-treatment waiting times. However this has been at the expense of shorter-waiting specialties whose waiting times have lengthened. All will need to improve when the elective recovery gets properly underway.

The converging waiting times at specialty level are reflected in the distribution of local specialty waiting times around the country, with waits generally getting worse over the past year while ultra long waits come down.

Referral-to-treatment data up to the end of March (the first month of the junior doctors’ strikes) is due out at 9:30am on Thursday 11th May.