In its own inimitable, haphazard, short-termist way, the NHS in England has been throwing plenty of effort at 18 week waits in the run-up to the General Election.

The right ingredients are there: the perverse admitted and non-admitted targets have been waived; extra money has been found to pay for extra capacity; and there has been a focus on reducing the total list size and treating long-waiters.

But (to continue with the cooking analogy) the preparation is lacking: the amnesties have been on-off-on-again; the extra money and capacity has been short-term, short-notice, and high-cost; and the reductions in list size have been target-driven and likely to include dollops of one-off validation and the cherry-picking of minor ops.

What the NHS really needs is enough baseline capacity to slightly exceed demand, a well-planned and fairly lengthy one-off effort to bring every waiting list down to size, and to treat all patients in a safe and fair order without the encumbrance of perverse targets. Do all that, and waiting times will take care of themselves.

Perhaps the next government will do the job properly (we can always hope). As things stand, the waiting list is growing long-term, and a longer queue means longer waits. So it is only a matter of time before the main 18-weeks target (the “incomplete pathways” one) is breached nationally. It might happen before the election, or it might happen after; we’ll find out when the February figures are released in April.

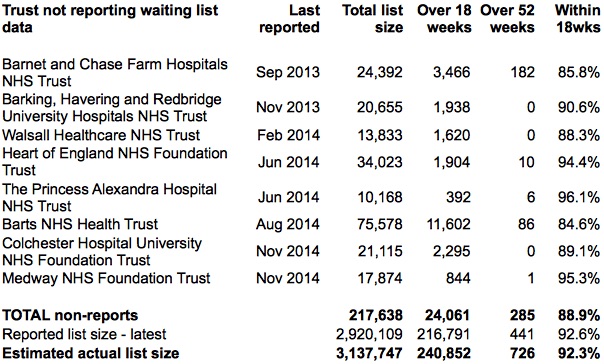

It’s going to be a close-run thing. At the end of January, 92.6 per cent of the waiting list had waited less than 18 weeks – the lowest since the 92 per cent target was first achieved in early 2012. If you include non-reporting Trusts, the real figure was probably just 92.3 per cent.

When February’s figures come out, it is even possible that the target might be achieved officially, but not if non-reporting Trusts are added back in. Now there’s a recipe for arguments across the Dispatch Box.

In the following analysis, all figures come from NHS England. If you have a national statistic that you’d like to check up on, you can download our Gooroo NHS waiting times fact checker.

England-wide picture

Royal Berkshire have started reporting their waiting list data again which is very welcome, but the other eight non-reporters are still absent.

The last reported data for the non-reporting Trusts shows that they were failing the main “incomplete pathways” target overall, so if you add them back into the official figures then national performance narrows from 92.6 per cent to just 92.3 per cent (against a target of 92 per cent).

Non-reporting Trusts are not included in the waiting list charts below. If they were, then the total waiting list size would remain almost constant during January (3,137,747 at the end of January, compared with 3,174,914 at the end of December). I estimate that the admitted patient target is unsustainable long-term when the waiting list is over about 3 million, and the main incomplete pathways target is unsustainable over about 3.3 million.

Admissions per working day were lower than last January, but close to the previous two Januaries. So there is little sign of the extra waiting list money resulting in extra admissions. The well-publicised pressures on emergency admissions will not have made elective admissions any easier.

The long-waits picture is hard to gauge because there are so many non-reporting Trusts. Of the 441 reported one-year-waits, some 217 were in orthopaedics at North Bristol.

The next chart shows both the size of the problem (the dark line) and the NHS’s response to it within the constraints of the perverse targets (the lighter lines).

The dark line shows that the waiting list has been edging ever closer to breaching the 18-week target, and is likely to breach in the next few months. Why? Well, long waits are a function of two things: the length of the queue, and the order in which patients are treated. Either can cause long waits, and both need to be under control to sustain short waits. So let’s look at those two things in turn.

The queue has been growing fairly rapidly for the last two years, and (in the absence of a long-term plan for more baseline capacity) the recent flurry of waiting list initiatives has at best only paused that growth. This long-term growth is the reason why an eventual breach is almost certain.

Turning now to the order in which patients are treated, ideally hospitals would treat urgent patients quickly, and the rest on a broadly first-come-first-served basis (i.e. starting with the longest-waiters).

But the perverse admitted and non-admitted targets restrict hospitals from treating their long-waiting patients, requiring them to devote most of their capacity to treating short-waiting patients instead. This causes queue-jumping and makes waiting times worse. In the past several months, there has been a series of partial amnesties on these two perverse targets. So the NHS has had greater freedom to treat long-waiting patients, and doing so has caused the ‘failure’ (very much in inverted commas) of the admitted and non-admitted targets that you see in the lighter lines below.

The amnesties have certainly helped to control long waits, and they have allowed waiting lists to be managed more fairly than before. But when the queue is growing long-term, a breach of the main target is still inevitable even if it happens a bit later.

Waiting times worsened in most specialties, and the decline in Orthopaedic and General Surgery waits is particularly notable.

The proportion of provider-specialties achieving the incomplete pathways target fell again in January to 77.3 per cent (from 79.5 per cent in December).

The decline remains focused more on longer-waiting services.

There was a welcome slight reduction in the number of services apparently managing their waiting lists perversely (by achieving the admitted and non-admitted targets, even though they consistently failed the incomplete pathways target).

Can this be attributed to an amnesty on the admitted patients target? I’m not sure; my understanding is that the latest amnesty was announced in a tripartite letter on 9th February which would have been too late to influence January’s practices.

Local detail

There are interactive maps showing the all-specialties position at every Trust and CCG. For specialty-level analysis at a particular Trust, independent sector provider or CCG, visit our 18-weeks reports page.

North Bristol remain at the top of the table with half of England’s one-year waits. Tameside are already moving themselves down the table following their reporting break, by reducing 92nd centile waits from 25.3 to 24.4 weeks; they’ve effectively swapped places with Lincolnshire.

Congratulations to Chesterfield for dropping out of the table from 7th to 36th place, by reducing 92nd centile waits from 23.5 to 18.0 weeks. Also to East Sussex, who dropped from 15th to 57th place (20.0 to 17.8 weeks).

Data for February 2015, the last month to be published before the General Election, is due out at 9:30am on 9 April. The March figures will be out a week after the Election on 14 May.